Written By Giles Ji Ungpakorn[1] from Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal

October 2013 – This article is an attempt to analyse the political situation surrounding the bloody civil war in “Patani-Southern Thailand” from the perspective of those who seek freedom, justice and self-determination. Unlike most academic papers or books on the subject, this article is not aimed at top politicians, military generals or officials of foreign powers, all of whom seek to maintain their own class interests by stressing “stability” or measures to “contain” the situation without any regard to the wishes of ordinary people.

According to the internal security organisation of the Thai state, since January 1, 2004, 5105 people have been killed and 9372 injured in the civil war in the South.[2] More than half of those killed were local ethnic Malays, which indicates that Thai security forces, in and out of uniform, are doing most of the killing.

In this paper, I refer to “Patani” or “Patani-Southern Thailand” as an historical unit covering the three most southern provinces which the Thai state created out of the destruction of the Patani sultanate. These are the provinces of Pattani, Yala and Naratiwart. The majority of the population in these provinces are Malay Muslims with their own language and culture.

Thai state as an obstacle to peace and self-determination

The violent conflict in Patani is caused by the process of Thai nation building and the subsequent colonisation of ethnically diverse communities into a centralised state, ruled directly from Bangkok, in the late 19th century. Thai nation building can be understood as an attempt by the rulers of Bangkok to create a modern centralised capitalist state, mirroring the colonial capitalist states which were being created by the British, Dutch and French in Burma, Malaya, Indonesia and Indo-China.[3] Most of these nation-building projects have led to conflicts between the periphery and the centre, since the new centralised political order destroyed previous forms of pre-capitalist regional autonomy.[4] The conflict in Patani is no exception.

Conflicts which are rooted in history need to be re-fuelled by continuing grievances and these grievances are the factors which explain why the people of Patani have little faith in the Thai state today. In comparison, these factors are missing in north or north-east Thailand, which though colonised by Bangkok in the same period of capitalist nation building, are not involved in a similar civil war. More will be said on these local grievances in Patani, but for the moment it is necessary to point out that unlike the north and north-east, the old Patani rulers and the entire Malay Muslim population of the area have been systematically excluded from mainstream Thai society, in terms of politics, culture and economic development. This explains the antagonism towards the Thai ruling class in Patani.

It will not come as a surprise to know that the Thai ruling class who control the Thai state have a political, economic and social interest in maintaining the present borders and preventing any separatist movements from splitting off areas which are currently within these borders. States always exists in relation to other states in the world, with more powerful states dominating weaker states in an “imperialist” fashion.[5] States also exist to control and rule over ordinary working people who make up the bulk of its citizens. As Lenin wrote in “State and Revolution”, the state is an instrument of class rule used to suppress other classes within society. Thus any sign of weakness, where a particular ruling class is seen to have to devolve power to others, or seen to lose control over certain areas, puts that ruling class at a disadvantage in relation to its international rivals and those who seek to challenge its rule from within. The Thai state is not a superpower, but it is jealous of its power over the population and resources within the present borders and it is also keen to act as a mini-imperialist with regard to weaker neighbouring states such as Lao and Cambodia.

Those states that rival Thailand in the region are the stronger states which are members of ASEAN, such as Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Burma, Vietnam and the Philippines.

For this reason, the main obstacle to the self-determination for the people of Patani, is the Thai state and its various constituents, especially the military. The Thai ruling class will not concede autonomy or independence for the people of Patani without a struggle.

Political struggles by mass movements, whether or not they are involved in armed struggles, strikes or mass protests, can be successful in forcing ruling classes to concede changes in the structure and the shape of the state. But ultimately change will be conceded by political decisions taken by politicians in consultation with other members of the ruling class. If these politicians are subjected to democratic elections and are accountable to the population it can be easier to change their minds.

The Thai military

The Thai military, in its present form, is a particularly powerful and intransigent component of the ruling class in terms of progress to peace and self-determination in Patani.

Many people have suggested that the military creates violent incidents in Patani in order to justify asking for an ever-increasing budget. As a body of men, the military benefit from this, often in a corrupt manner. Approximately 160 billion baht is being spent by the Thai state in Patani and 70% of this goes to counter-insurgency. The local economy of Patani, at 120 billion baht, is worth less than this bloated military budget. Even so-called “development projects” in Patani, such as road building, are given to military construction units.[6] Few local jobs for local people are created.

However, the main reason why the Thai military has an entrenched interest in opposing self-determination by the people of Patani is a “political interest”.

The military constantly intervene in politics, by staging coup d'états and changing constitutions. The latest coup d'état was in 2006, when the democratically elected and popular Thai Rak Thai government headed by Taksin Shinawat [also referred to as Thaksin Shinawatra] was overthrown.[7] The present army commander, General Prayut Junocha, feels able to state his political opinion in public, as though he was a leading elected politician, on many matters ranging from the war in Patani, to voting in elections and political reform. In 2010 he was responsible, alongside the military-appointed Prime Minsiter Abhisit Vejjajiva, for gunning down nearly 90 unarmed pro-democracy demonstrators in Bangkok.

Because of the long struggle for democracy in Thai society, undemocratic military intervention in politics needs to be specially legitimised. The Thai military does this by claiming that it alone is capable of protecting the monarchy and the unitary Thai state. Both the monarchy and nationalism are used by the military to justify its actions, with a myth created by the military that it serves the monarchy, when in reality it is the other way round.

The military gains from the fact that it can intervene in politics and commit state crimes against the people with impunity. Military economic interests include owning large sections of lucrative media outlets and having influence in state enterprises.

For this reason it is especially worrying that the Thai side in so-called “peace talks”, held between the separatist Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN) and the Thai authorities in early 2013, was headed and controlled by the military. The top Thai negotiator was Lieutenant General Paradon Pattanatabut, secretary-general of the National Security Council, and General Prayut Junocha rejected out of hand the BRN demand for self-rule, by stating that he would “never accept” any change to the unitary Thai state. Meanwhile, elected Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawat [or Shinawatra] kept quiet about the whole process. She is Taksin’s sister and the new head of Taksin’s Pua Thai [often also referred to as thePheu Thai] party. Since the election victory of Pua Thai in 2011, the government has gone out of its way to bow to the wishes of the military. One consequence of this is that it has accepted the military’s veto on any change to the draconian lèse majesté law and any release of prisoners of conscience who are in prison under this law for opposing the military coup of 2006.[8]

The hawks in the Thai state hope that the insurgents will surrender and that talks between the Thai and Malaysian governments, and between the Thai government and BRN “separatist leaders” will help towards this stabilisation. Afterwards they claim to want to attract business investment into the area. This policy is supported by top army generals, Yingluck’s Pua Thai government, the pro-military Democrat Party and it is similar to policies pursued by the Taksin administration before the 2006. These hawks talk in an abstract manner about the need for a “political settlement”, but because they refuse to consider the underlying root causes of the civil war, in practice they are only prepared to consider a military or security type solution.

General Sonti Boonyaratgalin, leader of the 2006 coup and Matupum Party leader, argued in November 2009 that “the pooling of resources and responsibilities of relevant agencies with a clear chain of command will create a breakthrough in the South”.[9] It did not and will never solve the problem of Patani. The Matupum Party counts among its members some Muslim politicians in the Wadah faction who were originally inside Thai Rak Thai, and before that, part of the Chawalit Yongjaiyut’s New Aspirations Party. Despite being co-opted into the mainstream Thai polity by people like retired general and Privy Council chair Prem Tinsulanon in the 1980s, they are now distant from the local population.

Of course, there is a contradiction in the position of the military towards the war in Patani. Most military commanders know deep down that they cannot beat the insurgents because they have local support and are able to carry out many operations freely.[10] The only strategy that they have is to try to contain the violent situation so that it does not get any worse. These people can only talk about making Thai state “command structures” more efficient. Meanwhile, ordinary soldiers, many of whom are recruited from the poor villages of the north-east, have no will to fight. They care nothing about “the protection of the nation” and try just to survive their tour of duty. However, some more intelligent military commanders with field experience, like retired General Chawalit Yongjaiyut, have supported the idea of special political autonomy for Patani.[11] Chawalit gained experience from the conflict with the Communist Party of Thailand in the late 1970s and understands that a political solution is necessary.

No political solution can be achieved while Patani is flooded by men with guns. Forty-five per cent of the Thai military is currently occupying Patani and added to this are the thousands of villagers who have been armed by the Thai state in so-called “village protection squads”. Apart from the army, paramilitary rangers and police, there are 3300 members of the Volunteer Defence Corps, 47,000 Village Defence Volunteers and 24,000 Village Protection Volunteers.[12] The Village Protection Volunteers are an exclusively Buddhist force, under the queen’s patronage.

The local population cannot possibly participate in political discussions about their future in this atmosphere of war, violence and fear. No political solution can be achieved while negotiations with the separatists are not run by elected politicians instead of the military.

In order to achieve a political solution and self-determination in Patani, the power and influence of the military in all aspects of Thai politics and society needs to be drastically reduced. The military budget needs to be cut to the bone and military officers removed from the media and state enterprises. Those who ordered the shooting of civilians in Bangkok and in Patani and those who staged coup d'états need to be brought to justice. These are the exact same factors required to build democracy, freedom and social justice in the rest of Thailand.

We can see that freedom in Patani is closely linked to freedom in Bangkok or other areas of the Thai state.

The question of violence

As a Marxist, I firmly believe that we have to side with all those who are oppressed by the Thai state. In practice, this means supporting the right of the insurgents to bear arms against the Thai state which has a long history of violent oppression in the Patani. Abstract calls for both sides to use “non-violence”, often voiced by NGOs, are not the solution. They merely end up by equating the Thai state’s violence with that of the insurgents and fail to question the legitimacy of the state to govern Thailand’s “colony” in Patani. Nevertheless, as a Marxist, I also believe that armed struggle is not the solution. The answer is mass mobilisations of people against the state. This must be encouraged whenever it happens in Patani.

The anti-war writer Arundhati Roy[13] once wrote that any government’s condemnation of “terrorism” is only justified if the government can prove that it is responsive to non-violent dissent. The Thai government has ignored the feelings of local people in the Patani for decades. It turns a deaf ear to their pleas that they want respect. It laughs in the face of those who advocate human rights when people are tortured. Taksin’s campaign to get people to fold paper birds to “forgive” the Patani people, whom he had just murdered at Takbai in 2004, and the farce of “returning” a copy of the Patani cannon, which was originally stolen by Thais, to the area, are some examples of the insults which originate from the Thai state.[14]

Under the emergency laws, no one in the South has the democratic space to hold political discussions. What choice do people have other than turning to violent resistance?

In another article, Arundhati Roy explained that we in the social movements cannot condemn terrorism if we do nothing to campaign against state terror ourselves. The Thai social movements have for far too long been engrossed in single-issue campaigns and people’s minds are made smaller by Thai nationalism.

Many talk about the need to involve “civil society” and NGOs in building peace in Patani. Yet who are these civil society actors? Are they those who wish for independence? Are they middle-class academics? Or are they NGO activists who constantly call for “peace” without challenging the nationalism of the Thai state?

Thai NGOs have an appalling history of siding with the military which staged the coup d'état in 2006. They attacked what they called the “dictatorship of the majority” in parliament and justified their alliance with royalists and the military by claiming that the majority of poor people who voted for the Taksin government “lacked knowledge and education”.[15] Thai NGOs cannot possibly have a positive role in solving the conflict in Patani.

History of Thai state repression in the South[16]

The nation state of “Thailand” was created by Bangkok’s colonisation of the north, north-east and south. However, what was special about the South was that the Patani ruling class was never co-opted or assimilated into the Thai ruling elite and the Muslim Malay population have never been respected or seen as fellow citizens since then. Bangkok and London destroyed and divided up the Patani Sultanate between them and Bangkok has ruled the area like a colony ever since.

1890s King Chulalongkorn (Rama 5) seized half of the Patani Sultanate. The Sultanate was divided between London and Bangkok under the Treaty of 1909.

1921 Enforced “Siamification” via primary education. Locals forced to pay tax to Bangkok.

1923 Belukar Semak rebellion forced King Rama 6 to make concessions to local culture.

1938 More enforced “Siamification” under the ultra-nationalist dictator Field Marshall Pibun.

1946 Pridi Panomyong promoted local culture and in 1947 accepted demands by Muslim religious leaders for a form of autonomy, but he was soon driven from power by a coup led by Thai nationalist military leaders.

Haji Sulong proposed an autonomous state for Patani within Siam.

1948 Haji Sulong arrested.

April 1948 police massacre innocent villagers at Dusun Nyior, Naratiwat.

1954 Haji Sulong killed by police under orders from police strongman Pao Siyanond.

1960-1970 Thai state policy of “diluting” the Malay population by resettling Thai-Lao Buddhists from thenorth east of Thailand in the Patani area. This was carried out under various military regimes, starting with Field Marshall Sarit Tanarat. Ban on the use of the Yawee Malay language in state institutions including schools.

State crime at Takbai

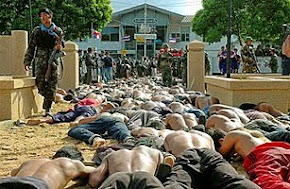

On October 25, 2004, Thai government security forces broke up a demonstration at Takbai in the southern province of Naratiwat. Apart from using water cannon and tear gas, troops opened fire with live ammunition above the heads of protesters, but some fired directly into the crowd, killing seven people and wounding many others, including a 14-year-old boy. There were villagers of all ages and sexes in the crowd. After this, the troops moved in to capture young Muslim Malay men. While women and children huddled in one corner, the men were stripped to the waist and their hands were tied behind their backs. The prisoners were made to crawl along the ground while troops rained kicks down upon their heads and bodies and beat them with sticks. Many of the prisoners were roped together in a long line and made to lie face down on the ground. The local military commander of the 4th Area Army[17] told a reporter on television that this action should be a lesson to anyone who dared to defy the government. “We will do this again every time”, he said. The whole event was captured on video, which only goes to show how arrogant and self-confident the security forces were.[18]

Finally, the bound prisoners were thrown into the backs of open-top army lorries, and made to lie, layer upon layer, on top of each other. Troops stood on top of their human cargo occasionally stamping on those who cried out for water or air and telling them that soon they would “know what real hell was like”.

Many hours later the first lorry arrived at its destination, Inkayut Army Camp. A number of prisoners who had been at the bottom of this lorry were found to have died in transit, probably from suffocation and kidney damage. Six hours later the last lorry arrived with almost all those on the bottom layers found to be dead. During those six hours between the arrival of the first lorry and the last one, no attempt was made by the authorities to change the methods of transporting prisoners. In total nearly 80 prisoners died. We must agree with a Senate report[19] on the incident which concluded that this amounted to “deliberate criminal actions likely to cause deaths” by the security forces. Prime Minister Taksin’s first response to the incident was to praise the security forces for their “good work”. Later the government claimed that the deaths were a regretful “accident”. Four years later on February 9, 2008, Prime Minister Samak Suntarawej told Al Jazeera television that the men who died at Takbai “just fell on top of each other”… “what was wrong with that?” Later in the same interview he lied about the October 6, 1976, massacre, saying that “Only one guy died”.

From October 6 to Takbai: Thai state’s culture of violent crimes

The lies told by Samak about Takbai and October 6 are clearly connected. Anyone watching the Takbaiincident would be reminded of October 6, 1976, massacre of students in Thammasart University.[20] In 1976, after attacking a peaceful gathering of students with automatic weapons, men and women were stripped to the waist and made by the police to crawl along the ground under a hail of kicks and beatings. Some students were dragged out of the campus and hung from trees, others were burnt alive in make-shift bonfires, mainly by right-wing thugs, some of whom were members of the ultra-right-wing Village Scout Movement.[21]

After both Takbai 2004 and October 6, 1976, government spokespersons told deliberate lies. One lie was that the security forces were “forced to act as the situation was getting out of hand”. In fact this was never the case. At Takbai, Senator Chermsak Pintong reported that the security forces admitted to a team of investigating senators that they broke up the demonstration in order to arrest 100 ring leaders, the names and photographs of whom were on a government blacklist. Under the 1997 constitution, Thai citizens were supposed to have the right to peaceful protest and were supposed to be innocent before trial. The actions of the police and army at Takbai show that they did not regard the local villagers as citizens. The demonstration was more or less peaceful until it was broken up violently by security forces. In the minds of the troops and their commanders, the Takbai prisoners were captured prisoners of war, “nasty foreigners” or “enemies of the state” who needed to be punished. So were the students at Thammasart in 1976.

After October 6, 1976, and Takbai 2004, government spokespeople also claimed that the trouble makers were foreigners and couldn’t speak Thai. In 1976 they were supposed to be Vietnamese.[22] In 2004 the state claimed that they were Arabs or Malays. All prisoners killed or captured in 1976, and at Takbai in 2004, were Thai-speaking Thai citizens. Government spokespeople also told lies that the students in 1976 and the demonstrators at Takbai in 2004 were well armed and posed a threat to security forces. There is no evidence to support this. No weapons were found at either site. At Takbai a rusty rifle, which had been lying in the river for years, was paraded as “evidence”.

After Takbai, the queen spoke of her concern for Thai Buddhists in the South. No mention was made of our Muslim Malay brothers or sisters. No mention was made of Takbai and worse still, the queen called on the Village Scout Movement to mobilise once again to save the country.[23] Luckily most village scouts are in their sixties and unlikely to commit violent acts anymore.

After the military coup of September 19, 2006, the junta’s prime minister travelled down to the Patani to “apologise” for what the Taksin government had done.[24] He announced that charges against some demonstrators would be lifted. Yet, his government, and the previous Taksin government, did not prosecute a single member of the security forces for the Takbai incident. No holder of political office has been punished either. To this day Thai officials can kill with total impunity. In 2007 the junta continued to emphasise the military “solution” in the South with a troop surge. In January 2007 the junta renewed the Taksin government’s southern emergency decree, which gives all security forces sweeping powers and immunity from prosecution.

Takbai was not the only violent incident to capture the news headlines. In April 2004, about 100 youths wearing “magical” Islamic headbands attacked police stations in various locations. But they were only armed with swords and rusty knives. They were shot down with automatic fire. Discontent was being articulated through a religious self-sacrifice. In one of the worst incidents that day, the army attacked the ancient Krue-Sa mosque with heavy weapons after the youths fled into the building. Ex-Senator Kraisak Choonhawan maintained that apart from the excessive force shown by the government, some prisoners in this event were bound and then executed in cold blood. He was referring to a group of youths from a local football team who were shot at point-blank range at Saba Yoi. The army officer in charge of the bloodbath at Krue-Sa was General Punlop Pinmanee. In 2002 he told a local newspaper that in the old days the army simply used to shoot rural dissidents and Communists. Now they send people round to intimidate their wives.[25] No state official has been punished for the events at Krue-Sa.

Torture and detention without trial

The military push in the South under the junta’s government, which started in June 2007, resulted in 1000 detentions without trial in the first two months. The military spokesperson for the “joint civilian, military and police command” in the South, General Uk Tiproj, claimed that those detained were people with “misguided beliefs who needed to be re-educated”. [26]

The Southern Lawyers’ Centre reported that between July 2007 and February 2008 there were 59 documented cases of torture by the security forces. In two incidents the torture resulted in death. In late January 2008 seven activist students from Yala were arrested and tortured.[27] Torture methods included beatings, being imprisoned, wet and cold, in air-conditioned rooms and the use of electric shocks.[28] According to the Lawyers’ Centre, most of the torture occurred in the first three days of detention, when prisoners were not allowed any visitors. The places where torture occurred were the Yala Special Unit 11section of the Yala Army Rangers camp and the Inkayut Army Camp in Patani. Needless to say, no one has been punished for killing and torturing detainees.

Violence and co-option

The root cause of today’s violence can be traced back to the creation of “Thailand” as a nation state in the 19th century. But the historical causes alone are not enough to explain the present civil war. Continuous repressive policies towards the local inhabitants by the Thai state over the years have refuelled resentment.

Duncan McCargo points out that the southern conflict is not a religious conflict between Muslims and Buddhists and that the Thai state has a tradition of murder, massacre and mayhem in the region. McCargo also shows that the Thai state has used a “dual track” policy of repression and co-opting local religious leaders and politicians in order to control the area, the latter especially in the period when Prem Tinsulanon was prime minister in the early 1980s[29] but also for a short time between 2004 and 2005 under Taksin Shinawat.[30]

By 1988 Thailand had become much more democratic with a fully elected prime minister and government. Local Muslim politicians were encouraged to join mainstream political parties, especially retired General Chawalit Yongjaiyut’s New Aspirations Party, where they formed a group known as the Wadah Faction.[31]

By the late 1990s Prem’s policy of co-opting local leaders was beginning to fall apart because it did little to solve the marginalisation of the majority of the Muslim Malay population and resulted in a gap opening up between grassroots people and their official leaders or representatives.

Those who wish to pin the blame for the violence on the Taksin government alone claim that he meddled in the security structures which were controlling the peace in the region. This is both unhistorical and completely ignores the fact that the unrest has been going on in various forms for over a century and that “peace deals” made by the Thai state in the mid-1980s with local elites were failing to address real grievances. Nevertheless, the Takbai and Krue-Sa massacres under the Taksin government had a big impact on the rise of the insurgency.

Unhelpful explanations about the violence in Patani

There are a number of irrelevant or unhelpful explanations for the violence in Patani. They all share a common thread which ignores and dismisses the oppression of the Muslim Malays by the Thai state. They also share the belief that the locals are somehow “incapable” of conducting a home-grown insurgency without outside instigation and support. As with most “elite theories”, history and conflict are confined to actions of the ruling elites while the general population are regarded as mainly ignorant passive spectators. Those who promote such theories wish to ignore the political and social causes of the civil war and concentrate on using military and diplomatic solutions to “end” the conflict while retaining existing state structures.

One theory claims that the violence is created by disgruntled army officers, afraid of losing a share of the lucrative cross-border black-market trade. According to the theory, these soldiers sponsor the violence in order to “prove” that the army is still needed. It is true that the military is involved in illegal cross-border trading and that if they were withdrawn from the area they would lose this lucrative activity. But this theory begs the important question about why soldiers occupy Patani as a colony in the first place, unlike the situation in the north or the north-east. It is also quite clear that there has been an insurgent movement throughout recent history and it enjoys support from important sections of the local population for real reasons.

Another theory claims that it is just the work of “foreign Islamic fanatics”, who have managed to brainwash some local youths into supporting a separatist movement. George Bush and Tony Blair’s encouragement of Islamophobia to support their invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq stirred-up such views and allowed human rights abuses against Muslims worldwide. But why would local youths just allow themselves to be brainwashed if there was not just cause? There is every indication that the insurgency is home grown for good reasons: there has been a history of state repression. Nevertheless, local insurgents and separatist movements have built links with sympathetic foreign governments and organisations.[32] This does not, however, indicate that the civil war is somehow instigated from abroad by “international Muslim extremists”.

Some academics have maintained that the violence started as a “patch war” between the royal palace, with the support of the army, and the Taksin government. Duncan McCargo[33] suggests that the southern violence can be explained as conflict between “Network Monarchy” and “Network Taksin”. McCargo also expanded this network conflict theory to include the conflict between the Red Shirts and the Yellow Shirts in other regions of Thailand after the 2006 coup d'état.

This is similar to the attempts to explain the September 19 coup d'état as a conflict between “feudalism” and “capitalism”, along old Stalinist lines. It is true that the Taksin government wanted to reduce the role of the military in controlling Patani and transfer many powers to the police. But this was more about his attempts to “regularise” governance in the region and also to stamp out the black market, a policy pursued in other parts of the country. This undoubtedly caused resentment among the army, but it does not explain the main underlying causes of the civil war.

The “network conflict” is an elite, top-down view of events which denies any role by ordinary people. It denies any reason for Malay Muslims to be antagonistic to the Thai state. Neither can it explain the general political crisis and conflict between Red Shirts and Yellow Shirts following the 2006 coup d'état.[34]

Who are the insurgents?

Back in the 1970s a clear separatist movement existed, cooperating in its struggle against the Thai state with the Communist parties of Thailand and Malaysia. The Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN) was established in 1963 and the Patani United Liberation Organisation (PULO) was founded in 1968.

PULO are not in a position to control much of what is happening on the ground today. One PULO activist admitted to the BBC that, “Right now there is a group which has a lot of young blood. They're quick and fast and they don't worry what will happen after they do something. They don't care because they want the Government to have a big reaction, which will cause more problems.”[35]

By 1984 the BRN had split into three. One organisation which originated from the BRN is the Barisan Revolusi Nasional-Koordinasi (BRN-C). By 2005 the Runda Kumpulan Kecil (RKK or Patani State Restoration Unit) was becoming more prominent in the insurgency. It is believed to be a loose grouping of people from the BRN-C who trained in Indonesia. There seem to be many organisations operating today. They do not claim responsibility for their actions because by deliberately not claiming responsibility they make it extremely hard for the Thai Intelligence services to understand who is who and which of the various organisations is taking what action.[36] This has been described by journalists as a “war between the Thai army and ghosts”.

The Patani insurgency follows the patterns of many Middle-Eastern struggles against Western imperialism and local despotic ruling classes. In the 1960s and 1970s they were secular movements allied to Communist parties. But with the decline of the Communist parties, partly as a result of their collaboration with local despots, especially in the Middle East, rebels and insurgents turned to new forms of ideology, mainly radical Islam.[37] This explains why radical Islam is the banner under which the present day insurgents fight. It is not the rise of radical Islam which has caused the violence. The brutal actions of Thai governments and the failure of the Communist Party of Thailand (CPT) have pushed radicals into adopting Islam.

Listen to local people

When considering the violence in Patani, we need to listen to what local people are saying. Local Muslim people do not generally hate their Buddhist neighbours. The civil war never started as “communal violence” between people of differing religions. This is still the case now, despite the counter-productive efforts by Thai governments in saturating the region with arms, including the arming of local villagers.

Public spaces such as Buddhist temples and schools have also been militarised by the Thai state. Some Buddhist monks have been brutally killed and in June 2009 armed Buddhists gunned down praying Muslims at the Al Furqan Mosque. It is thought that they were led by an ex-military ranger. Apart from soldiers and rebels, local traders, rubber tappers, priests, Imams, ordinary villagers, school teachers and government officials have all been victims of violence. Most of those killed have died at the hands of the security forces.

In the late 1990s most local people were not really demanding a separate state. Thai government violence may now have pushed people towards supporting separation. Patani has been neglected economically and when there has been development it has not been the majority of local Malay Muslims who have benefited. There is a high level of unemployment in the area and many people seek work in neighbouring Malaysia. Nevertheless, economic development alone cannot solve the violence.

What local people are saying more than anything is that they want respect. Their religion, language and culture are not respected by the Thai state. The state education system emphasises Thai, Buddhist and Bangkok history and culture. This is why schools are often burnt. In the past 60 years successive Thai governments have arrested religious leaders, banned the teaching of yawee (the local dialect of Malay spoken in the area), closed religious schools, forced students to learn the Thai language, forced students to wear Thai-style clothes, encouraged people to change their names to “Thai” names and forcibly changed the names of local districts to “Thai-sounding” names. All this has been carried out by Bangkok governments which maintain an occupying army in the southern border provinces.[38]

In the 1960s and 1970s the military dictatorships settled some Buddhist north-easterners in the South in order to “strengthen” the occupation.[39] It reminds one of the British policy in Northern Ireland or Palestine. Buddhist temples were built in predominantly Muslim areas. In this period there were times when Muslims were made to bow down before Buddha images. Even now they are made to bow down before pictures of the king, which is an offence to their religion. There are house searches by troops using dogs. Again this is an insult to Muslims. Recently soldiers were conscripted to become monks in southern temples and the temples have army guards.

The occupying army and the police are feared and hated. Local people know that their sons, brothers and fathers have been taken away at night, then tortured and killed by the Thai army and police, often in plain clothes.[40] In 2004, the defence lawyer Somchai Nilapaichit, who was a key human rights activist on this issue of torture, was kidnapped in Bangkok and killed by police from different units. He was trying to expose police tactics in torturing suspects into confessions about stealing guns from an army camp in early 2004. The involvement of police from different units in his murder indicates a green light from above: from Prime Minister Taksin and others in his government. To date, no one has been punished for Somchai’s murder and his body has not been found.

It isn’t hard to find green lights, right at the top, for Thai state violence. No one has been punished for the 1976 bloodbath at Thammasart, the May 1992 massacre or for the killings at Takbai or Krue-Sa in 2004. The Taksin government also sanctioned the extrajudicial murder of over 3000 “drug suspects” in its war on drugs. Many were killed in Patani, others killed were among northern ethnic minorities. The king approved of the war on drugs and the October 6 massacre. The military-installed Democrat Party government contributed to further state crimes in 2010 and together with the army generals, sanctioned the shooting of pro-democracy civilians in Bangkok. The courts have always protected those in power and offer no justice.

After the February 2005 election Taksin’s party lost almost all seats in the South because of its policies, especially the Takbai incident. But it gained a huge overall majority nationally. The government established the National Reconciliation Commission under ex-prime minister Anand Panyarachun. He had served as a civilian PM under a military junta in 1991. Most people in the Patani doubted whether this commission would solve their problems. Anand was quoted in the press as saying that self-rule and autonomy were “out of the question” and that people should “forget” the Takbai massacre.[41]

Despite Anand’s remarks, the report of the National Reconciliation Commission came up with some progressive statements and suggestions.[42] First, it stated that the problems in the South stemmed from the fact that there was a lack of justice and respect and that various governments had not pursued a peaceful solution. It went on to describe how the Thai Rak Thai government had systematically abused human rights and was engaged in extrajudicial killings. The commission suggested that local communities in Patani be empowered to control their own natural resources, that civil society play a central part in creating justice and that the local Yawee language be used as a working language, alongside Thai, in all government departments.

The latter suggestion on language is vital if local people are not to be discriminated against, especially by government bodies.[43] Yet it was quickly rejected by both Taksin and Privy Council chair General Prem Tinsulanon.[44]

The weakness of the ‘armed-struggle’ strategy

The insurgent strategy of using “ghosts” to attack the Thai security forces and then not claiming responsibility might have some military advantages, but such advantages are massively out-weighed by the political disadvantages. By not claiming responsibility for attacks on “legitimate military targets” and confining attacks to such targets, the insurgents allow the Thai military to use death squads, usually out of uniform, to attack and kill local activists and ordinary civilians who are on government blacklists. The government and mainstream media can then paint a picture of the insurgents as “armed gangsters” who kill people indiscriminately. This spreads fear among the local civilian population and is counter-productive to building real mass support among local villagers and also among the general Thai population in other regions. The ghost war strategy plays into the hands of the Thai state’s dirty war.

The Patani insurgents cannot hope to beat the Thai military in a military struggle. They are significantly less well armed and funded and the local population which might support the insurgency is a small minority of the population within the current Thai state.

To make any political progress towards liberation and self-determination, the Patani movement needs to build a mass political party which can operate legally and put forward political demands which go beyond just “Patani nationalism”. The party would have to address economic and social issues and be capable of winning support from local Thai Buddhists and also capable of winning solidarity from social movements in the central, north and north-eastern regions of Thailand.

Mass political action is the answer

The resistance today is not just about planting bombs and shooting state officials. Communities act in a united way to protect themselves from the security forces who constantly abduct and kill people. Women and children block the roads and stop soldiers or police from entering villagers. On September 4, 2005, they blocked the entrance to Ban Lahan in Naratiwat and told the provincial governor that he and his soldiers were not welcome in their village.[45] Two weeks later villagers blocked the road to Tanyong Limo. Earlier two marines had been captured by villagers and then killed by unknown militants. Villagers suspect that the marines were members of a death squad sent in to kill local people.[46] The villagers held up posters aimed at the authorities, saying: “You are the real terrorists.” In November 2006, villagers protested at a school in Yala, demanding that troops leave the area. One of their posters read: “All you wicked soldiers … get out of our village. You come here and destroy our village by killing innocent people. Get out!”[47]

Many slogans against the military are painted on roads. In August 2007 “Darika”[48] made a note of some:

“Peace will come when there are no soldiers.”

“We don’t want the soldiers in our village. We are afraid.”

“Without the soldiers, the people will be happy.”

“The curfew is unjust. They are killing innocents.”

Such protests in villages continue to occur today after various incidents involving the security forces.

On May 31, 2007, the Student Network to Defend the People organised a mass rally of 3000 at the Patani Central Mosque. The rally started because of four murders and one rape carried out by Army Rangers at a village in Yala. The demands of this peaceful protest were for a total review of government policy in the South and a withdrawal of soldiers from the area.[49]

Assistant professor Dr Srisompop Jitpiromsri from Songkla University reported that between 2005 and 2008 there were a total of 26 mass demonstrations in the Patani. Thirteen of them were to demand the release of detainees and another five demanded that troops and police leave the area. These mass actions by villagers and students are the real hope for freedom and peace in the South. Yet the Thai state and the mainstream media brand these mobilisations as “violent”. They make no distinction between peaceful social movements and the armed insurgency. The arrest and torture of seven Yala student activists in 2008 confirms this point.[50]

If the mass action of these social movements is to succeed, we must give them every encouragement and support.

Conclusion

It should be obvious that the struggle for self-determination in Patani is closely connected to the struggle for democracy and freedom in Thailand as a whole. For both to be achieved, the power and influence of the Thai military needs to be reduced and draconian laws which limit freedom of expression, such as the emergency law and the lèse majesté law, must be repealed. Social movements with mass support and a willingness to engage in solidarity between issues and struggles will be crucial. Unfortunately the Red Shirt movement, which was Thailand’s largest social movement for democracy in recent years, has fallen in behind the Pua Thai government which is reconciled with the military. The UDD leadership of the Red Shirts must take much responsibility for this betrayal.

Unless a new pro-democracy movement which is independent from Pua Thai and the military and is willing to reject conservative Thai nationalism can arise, the path towards self-determination in Patani and freedom and democracy in the other regions of Thailand will be a long one.

In the short term, we must demand the removal of Thai troops from Patani and a general demilitarisation of the area. Emergency security laws should also be repealed and standards of human rights have to be established in Patani and regions of Thailand to the north, by punishing state crimes and releasing political prisoners.

Change may be difficult, but it is not impossible. Unlike present-day constitutions, Thailand’s first constitution after the 1932 revolution against the absolute monarchy did not stress the unitary Thai state. It stressed the political sovereignty of the people. Pridi Panomyong’s government in 1947 also accepted the principle of autonomy for Patani. We need to fight for those principles today.

Notes

[1] Giles Ji Ungpakorn is a political commentator and dissident. In February 2009 he had to leave Thailand for exile in Britain because he was charged with lèse majesté for writing a book criticising the 2006 military coup. He is a member of Left Turn Thailand, a socialist organisation. His book, Thailand’s Crisis and the Fight for Democracy, will be of interest to activists, academics and journalists who watch Thai politics, democratisation and NGOs. His website is at http://redthaisocialist.com/. Email:ji.ungpakorn@gmail.com.

[2] Kom Chat Luk newspaper, May 1, 2013.

[3] Giles Ji Ungpakorn (2010)“Thailand’s Crisis and the Struggle for Democracy” (2010). WD Press, U.K.available at http://www.scribd.com/doc/47097266/Thailand-s-Crisis-and-the-fight-for-Democracy.

[4] Martin Smith (1999), Burma. Insurgency and the politics of Ethnicity. Zed Books, London; David Bourchier & Vedi Hadiz Eds (2003), Indonesian Politics and Society. A Reader. Routledge-Curzon; Christopher Duncan (2004), Civilizing the Margins: Southeast Asian Government Policies for the Development of Minorities. Cornell University Press.

[5] Alex Callinicos (2009), Imperialism and the Global Political Economy. Polity Press, Cambridge, U.K.

[6] Rough figures from Adam John, PhD economics candidate at the Agricultural and Food Policy Studies Institute at Universiti Putra Malaysia in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, given at “To understand the conflict; Patani-Thailand South" seminar in Lund August 31, 2013, organised by the Peace Innovation Forum, Focus Southeast Asia.

[7] Giles Ji Ungpakorn (2010), already quoted.

[8] See Giles Ji Ungpakorn (2011)“Lèse Majesté, the Monarchy, and the Military in Thailand”. Paper given at the Department of Peace and Conflict Studies (Pax et Bellum), University of Uppsala, Sweden, April 29, 2011. Available at: http://redthaisocialist.com/english-article/72-academic-papers/187-lese-majeste-the-monarchy-and-the-military-in-thailand.html, or http://www.scribd.com/doc/54529804/Lese-majeste-the-Monarchy-and-the-Military-in-Thailand

[9] Bangkok Post 19/11/2009.

[10] Poldej Binprateep, an under-secretary at the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security in the junta’s government, admitted this. http://www.prachatai.com/15/1/2007 (in Thai).

[12] International Crisis Group (2009), “Southern Thailand: Moving Towards Political Solutions?” Asia Report N°181 –December 8, 2009.http://www.crisisgroup.org/library/documents/asia/south_east_asia/181_southern_thailand___moving_towards_political_solutions.pdf.

[13] Arundhati Roy (2004), The ordinary Person’s Guide to Empire. Harper Perennial.

[14] The cannon was promptly blown up by insurgents.

[15] Giles Ji Ungpakorn (2009), “Why have most Thai NGOs chosen to side with the conservative royalists, against democracy and the poor?”. Interface: a journal for and about social movements. Volume 1 (2): 233-237 (November 2009). http://groups.google.com/group/interface-articles/web/ungpakorn.pdf.

[16] Nik Anuar Nik Mahmud (2006) The Malays of Patani. The search for security and independence.School of History, Politics and Strategic Studies, University Kebangsaan, Malaysia; Tengku Ismail C. Denudom (2013), Politics, Economy, Identity or Religious Striving for the Malay Patani. A case study of the conflicts: Thailand-Pattani. Peace Innovation Forum, Focus Southeast Asia, Lund, Sweden.

[17] Lt-General Pisarn Wattanawongkiri was the Fourth Army Region Commander at the time.

[18] See the video at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=seSIT8nfPg0

[19] Thai Senate Committee on Social Development and Human Security, December 2004.

[21] Katherine Bowie (1997), Rituals of National Loyalty. An Anthropology of the State and Village Scout Movement in Thailand. Columbia University Press. Giles Ji Ungpakorn ed. (2003), Radicalising Thailand: New Political Perspectives. Institute of Asian Studies, Chulalongkorn University.

[22] A claim made by Samak Suntarawej and others.

[23] Post Today 17/11/2004 (in Thai).

[24] Prime Minister Surayud needs to apologise for what he did back in the May 1992 crack-down on unarmed pro-democracy demonstrators in Bangkok!

[25] See Pasuk Phongpaichit & Chris Baker (2004), Thaksin. The business of politics in Thailand.Silkworm. Page 19.

[28] Turn Left, March 2008, www.pcpthai.org/ (in Thai).

[29] Duncan McCargo (2008), "What’s Really Happening in Southern Thailand?" ISEAS Regional Forum, Singapore, January 8, 2008; Duncan McCargo (2009), "Thai Buddhism, Thai southern conflict". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 40(1): 1-10; Duncan McCargo (2009), "The Politics of Buddhist identity in Thailand’s deep south: The Demise of civil religion?"Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 40(1): 11-32.

[30] Duncan McCargo (2012), Mapping National Anxieties. Thailand’s Southern Conflict. NIAS Press.

[31] Carlyle A. Thayer (2007), Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Literature Review.http://www.scribd.com/doc/17965033/Thayer-Insurgency-in-Southern-Thailand

[32] Carlyle A. Thayer (2007). Already quoted.

[33] Duncan McCargo (2005), “Network monarchy and legitimacy crises in Thailand”. The Pacific Review18 (4) December, 499-519; Duncan McCargo (2012), already quoted.

[34] For an explanation of the Thai crisis, see: Giles Ji Ungpakorn (2011), “Thai Spring?” Paper given at the 5th Annual Nordic NIAS Council Conference organised by the Forum for Asian Studies/NIAS. November 21-23, 2011, Stockholm University, Sweden. http://redthaisocialist.com/english-article/72-academic-papers/296-thai-spring.html or http://www.scribd.com/doc/73908759/Thai-Spring

[35] Interview with the BBC’s Kate McGeown, 7/8/2006. http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/.

[36] Zachary Abuza, “Terrorism Monitor”, 8/9/2006 James Town Foundation.

[37]Chris Harman (1994), “The Profit and the Proletariat”. International Socialism Journal 64.

[38] Ahmad Somboon Bualuang (2006), “Malay, the basic culture”. In The situation on the Southern border. The views of Civil Society. Published by the Coordinating Committee of the Peoples Sector for the Southern Border Provinces (in Thai).

[39] There have been some Buddhists living in the region for centuries.

[40] Akerin Tuansiri (2006), “Student activities in the violent areas of the Southern border provinces”. InThe situation on the Southern border. The views of Civil Society. Already quoted (in Thai).

[41] Bangkok Post, 10/8/2005 and 9/5/2005.

[42] National Reconciliation Commission, 16/5/2006 (in Thai).

[43] This proposal was supported by the Malaysian politician Anwar Ibrahim.http://www.prachatai.com/5/5/2009 (in Thai).

[44] Bangkok Post, 26/6/2006 and 27/6/2006.

[48] Darika (2008), “Records from Kollo Balay village. A Village in the Red Zone”. South See 5, Social Research Centre, Chulalongkorn University (in Thai).

[50] http://www.prachatai.com/2/2/2008 (in Thai).

Labels:

Politic

Labels:

Politic

Previous Article

Previous Article

Responses

0 Respones to "Thailand: The bloody civil war in Patani and the way to achieve peace"

Post a Comment